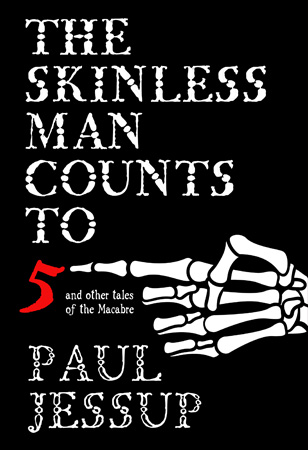

To celebrate the release of Paul Jessup’s new collection of short fiction, The Skinless Man Counts to Five, we’ve wrangled a little Q & A out of the author.

Underland: Assembling a collection is like making a mix-tape. We don’t really make them anymore now that everything is streamed, but back in the day, curating the perfect selection of songs, in just the right order, was a real art. The same seems to be true for a collection of stories. It needs a rhythm, almost like breathing. So, what was going through your head as you were collecting and arranging the stories in Skinless Man, seeing as they span such a huge swath of your writing career.

Jessup: I guess you could say creating playlists these days is a little like creating a good mixtape. Though probably not quite as particular about the order of the songs, since most of us just put it on random! When creating this book, I guess it could be read as both playlist and mixtape. It would work just as well when read out of order (eg: on shuffle), or one story right after the other (as a mix tape). It’s a tricky thing to get right, but I know people read collections like this in different ways. I’m a shuffle person, I don’t read the stories one right after the other in order. I dip and dive, picking stories out at random, or when they seem interesting, or just by title alone. I figured you’re going to have some people like me, and have some others with a bit more control over their impulses.

As for figuring out which stories to include, that felt obvious to me from the start. I’ve had several favorites that I knew had to be in, no questions asked. Once I looked over those favorites, and compared them to some new stories I wanted to include, I realized that this collection seemed to focus mostly on horror. Surreal horror, yes. Weird fiction and weird horror, most certainly. Some of the stories were scifi horror, some were fantasy, but the majority I wanted to put in this collection were dark and strange and unsettling.

It’s odd to look over your career and see that being the case. You think in twenty plus years, I would have more of a wider range, but…

No. The non-horror (as much as I love them) stories are fewer and further between then the rest. So for this collection I decided to focus on that, which meant leaving out a handful of stories that I really loved, but seemed out of place with the greater collection itself (“Mister Waterbones and His Wife,” “The Last Dryad,” and “Music of Ghosts” being three I loved but had to leave out).

After that, putting them together in a sort of order became trickier and trickier. The first story was key. “House at the End of the World” is an interesting one, when I first finished writing it, it plainly freaked me out. I thought I went too far with the ending. It got under my skin. I actually went back and forth for decades trying to decide if I liked the story or hated it because it disturbed me that much. In recent years I realized that its precisely why *I loved* that story. That it went beyond like or hate, that it was so unsettling that I loved it without even realizing it. Which, I think, can be the cornerstone to good horror. And why, I think, it had to be the key to this collection and the first story.

The last story was pretty obvious, it had to be the titular story in this collection. I knew that without even a second thought! And then those two decisions helped me plan the structure and layout of the rest of the book. The first one was surreal, uncanny, and weird. The last one was surreal and far-future science fiction. I could have it move, then, from super surreal folklore to modern day surreal horror, to near future dystopian horror, to far future horror at the end. In the middle there is some dabbling bits with lovecraft and sword and sorcery, which leans into post-apocalyptic, which I think fits well into dystopian, though goes further into the fantastic than the other stories.

With this, we get a themic rhythm, like ocean waves, moving from story to story to story, until they crash on the ending, that last final one, that hopefully leaves the reader with this itchy feeling under the skin that the world is all broken and sideways.

Underland: Speaking of themes, this collection meditates a lot on the idea of transitions—of liminal spaces between this world and the one in the mirror or the one in the walls or the one behind everyone’s social masks. Many of your stories end with a character making a transition—not necessarily a good one, but an alteration of the way things were that can’t be undone, and usually painted with the surreal horror paintbrush you mentioned above. Is this something you ever find yourself consciously contemplating or do you just naturally feel drawn to change and the uncanny?

Jessup: It’s something I feel drawn to, and I’m not exactly sure why. Something appeals to me about the uncanny, it lights up my brain in such strange, sinister ways, and I can’t seem to get enough of it. Maybe it was reading MR James, Machen, and Poe at too early an age? Yet, that doesn’t seem right, either. Because I was drawn to their works because I was already drawn to the uncanny and the liminal. I seek it out in my own experiences, ever since I was really little, early moments and memories of times before I could read or write, going into haunted house rides and wanting to live in that moment, when things are between the outside world and the inside. That cart moving in the darkness, always on rails, always moving forward through the displays of creepy and gothic things.

Or maybe it was something else, uncanny moments in all points of my life. Things that I could shake off later as a dream, or something unreal, and yet, I knew I had experienced it. Even if I didn’t want to experience it. A blue lady walking out of my closet in the middle of day when I was about three or four. My brother sleeping under the bed while it happened, unable to wake up to see until it was too late. Or even just liminal spaces themselves, drawn to them, sucked into their vortex. Something appeals to me about being between two states, it’s like standing in the middle of a rushing river, always changing.

I remember all of my walks through the woods I had near my house growing up, and finding the ruins of a house, now just a basement and a skeleton of walls, no roads going to and from. Or climbing on the rusted old remains of an oil refinery while the sunset in the distance. These were things that existed, once, but were ghost now. In between states, like smoke from a fire. Neither solid, nor liquid, but somehow caught between the two.

Something about that appeals to me. The same with characters in stories, always in flux, always moving. Changing, becoming something else, someone else. I guess that’s the true nature of story, when you get right down to it. Something changes, someone changes. And in real life, you can’t unwind time, you can’t change back into who you were before. You could only go further on, changing into something else. I guess in a way, that can be seen similar to the Tibetan Book of the Dead, how when your ego is stripped away it can either be terrifying or freeing, depending on your point of view.

And that’s what happens in these liminal states. It’s like in Alice in the Looking Glass, when she goes into the forest without names and forgets herself, and who she is. That is the removal of the ego, the identity, the self that is the mask hiding all else. But there are other forms of change, too. Sometimes new masks are added, forced onto us, and there is more terror there than anything else. The liminal state can be key in those moments, to flow away, to follow that river somewhere else.

Underland: Speaking of masks, they come up quite literally in your short fiction, again and again. As with your attraction to liminal spaces and border experiences, what do you think it is about the characters in your fiction that makes you want to mask them?

Jessup: Oh yes, masks do make people liminal, don’t they? You can see the person, but you can’t know for sure who is under the mask. And masks change us, too. Anyone putting on a mask starts to act differently, more inspired by the mask, cloaking who they are. Even people who aren’t actors, they start slipping into a character and start slipping out of themselves. It’s a dangerous thing, being able to change yourself, cloak yourself, and unmake yourself. It’s terrifying to me, on several different levels.

One key level, I think, is not knowing who a person is, and that’s uncanny valley. They look familiar, but changed. Another is changing yourself, either on purpose or having someone do it to you. There will always be a bit of the mask behind, floating around inside of you. The worst kind of mask is the one imposed by others, by society who wants to change you and mold you in their image. I think that’s the fear of the first story in the collection, having the agency of identity stolen from you, and forced to become someone else, someone other. Something more terrifying.

Underland: In closing, let’s talk about how life influences art and vice versa. I think, after reading this collection, readers will truly see the scope of the uncanny and the fantastic in your work. It’s very weird-forward, more so than other bodies of work that cohabitate in this liminal space with you. While we all understand how our life experiences take shape on the page, almost the way dreams come together, how do you think your work influences your daily life, in reverse. Thinking and writing and creating in this mode can’t just be a thing you turn on and off. Does it color your world? How do you see yourself and the rest of us on this rock through your creative lens?

Jessup: Oh, it’s definitely not something turned on or off, but instead a constant way of existing. My mind is always turned up to 11, and seeing things in strange surreal permutations. I seek out the liminal, the borderline, the weird. I overhear conversations at the table next to me, and taken out of context they become surreal poetry. I name houses on my street during my walks things like the witch house, the ghost house, the chain house, all based on the vibes they give off. I explore, and crawl under the city by following the rivers and creeks that crawl under houses, and towards the woods beyond. I’m sure we’d all had moments in our lives when they felt more like a dream than a real thing, and I tend to seek these out. They remind me of how slippery this world really is, and how any moment it all might just change in the blink of an eye.

Sitting outside your window, and hearing someone singing in the fog, but when you look outside it’s just the shadow of a dog, running. Going out for long walks and finding streets that are empty, no cars, no people, just still and lonesome houses. My mind tends to feed on these things, relish them and savor them. This whole world is weird and surreal and strange, we just have to look for it in a certain way. To be open and ready to receive the terrifying wonder of the everyday. And it is terrifying in a way, to realize how unstable our constructed view of reality is. We want it to be rational, to be built up out of rules and math and science.

But it’s not, the world doesn’t care about what we want. It just exists, all wonderfully strange and slippery.

The Skinless Man Counts to Five and Other Tales of the Macabre is available now from the Underland Shop.