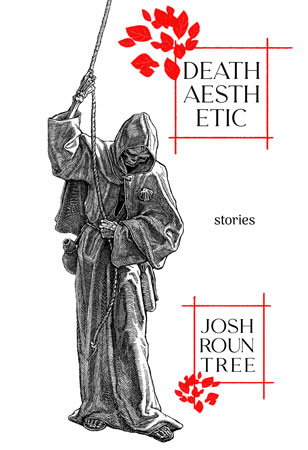

To celebrate the release of Josh Rountree’s new collection, Death Aesthetic, we’ve wrangled an interview with the author about some of the inspiration behind his stories.

Underland: There are a number of stories that center around children dealing with the consequences of parents’ actions. Was there any particular event or memory that inspired this narrative choice?

Rountree: Well, my parents divorced when I was a toddler, and afterward they lived in different parts of the state, so that’s certainly something that shaped the person I became. But there was no specific incident that really inspired these stories in that way. More of a memory of the unsettling nature of childhood, and I guess remembering what it’s like to deal with that sort of instability at a young age.

I was a nervous kid. To be fair, I’m a nervous adult. And I remember always worrying about everything, whether there was cause for concern or not. Gen X has this reputation as a generation of latchkey kids, and I was certainly one of them. Like I mentioned in the notes for one of these stories, I grew up as kind of a feral kid in a small town, sneaking out of the house, roaming the streets. Probably causing more trouble than I should have. And while I had plenty of folks looking after me, there was never much oversight on where I went when I left the house, and what sort of danger I might be chasing down.

That danger, real or imagined, is at the heart of these stories I write about kids.

I love to get into the heads of kids who are getting in a little to deep. Kids trying to figure out why life already seems to be skidding off the road, and they don’t know how to recover. They relish every risk they take, and don’t think much about the consequences. At least until that moment when they figure out that grownups can’t bail them out of everything. Can’t magically undo whatever mistakes they might make. Grownups, in fact, don’t have things figured out nearly as well as you imagined they did, when you were just a little bit younger.

It’s tough navigating your way to adulthood. And that journey is perfect story fodder.

Underland: Several stories feature someone being buried alive, which I find absolutely terrifying. Does this come out of a personal fear or something else?

Rountree: No, that’s not a particular fear of mine. I’m not even claustrophobic. I mean, obviously the thought of being buried alive is terrifying and awful. I don’t want to volunteer to be buried. But it’s not a fear I dwell on in any significant way.

Looking back at these stories, I think it’s interesting that none of them portray being buried alive as an entirely bad thing. In the first story, “See That my Grave is Kept Clean,” it’s almost a blessing. A gift from the dead, in some ways. And in “Their Blood Smells of Love and Terror,” people are sacrificed to the grave, but the grave also gives one character the opportunity to perform a selfless act.

I think in both cases, going to the grave isn’t the end for these characters, and I guess that’s what I’m getting at with this whole collection.

Underland: The theme of transformation runs through the collection. Do you see transformation as a sort of wish fulfillment gone awry?

Rountree: I think I see transformation as something to be wished for. A way to avoid stagnancy and to be the person you want to be. Transforming ourselves can be terrifying and strange, and it takes a lot of effort to overcome the sort of inertia that sets in over our lives. But you’ve got to be true to who you are.

By the time we get to a certain age, our notions of self are pretty much set in stone. But that doesn’t mean we can’t change our minds. There’s no reason we have to be the same person forever. A lot of times, this comes down to the realization that you never really knew who you were at all, and you’ve found a version of yourself that fits a whole lot better than the old one. Transform however you want – emotionally, physically, spiritually. Otherwise, you’ll always be chasing some part of you that’s just out of reach.

There are a couple of examples of forced transformation in these stories, and that’s where things get frightening to me. Taking away someone’s choice to be who they want. Forcing them to look the way you want them to, to think the way you do. That’s more than a little bit evil. Stories like “We Share Our Rage with the River” where mermaids are captured and transformed into obedient wives who must walk on land, and “The Cure for Boyhood” where a boy’s parents go to extreme lengths to keep him from becoming his true self – in both cases, things don’t work out so well for those who try to take those decision away from someone else.

Let people be who they want to be; you be who you want to be.

Easy, right?

Underland: In “The Green Realm” you leave the interpretation of events up to the reader. Without giving too much away, what was the thought process in not spelling things out?

Rountree: The short answer is, I love ambiguous endings.

It seems like there used to be more room for this sort of thing in fiction, but more and more we seem to be tying our stories up with neat little bows. Overexplaining some things that might be better left as mystery. I believe that leaving the ending up for interpretation causes the story to resonate longer with the reader. Hopefully if you do it well, people will turn the story over and over in their head for a long time, grasping at whatever truth they need to find.

You have to play fair with the reader though. Ambiguous doesn’t mean just ending the story with no resolution whatsoever.

In the case of “The Green Realm” we know from the very beginning that our protagonist has screwed up his life, and we backtrack to his youth to find out how things derailed so badly. We find that he’s been searching for an elusive sort of happiness that he can never quite get his arms around, and I’m hopeful that the ending causes that same sort of feeling in the reader. There’s a melancholy nostalgia here for missed opportunities and wasted years. And there’s no way for any of us to travel, except forward.

As for what is, or is not, in the woods. You tell me.

Underland: How did you choose the order of the stories for this collection?

Rountree: Often writers don’t realize what sort of themes we’ve been working at until we’re able to step back and take a look at a whole chunk of our assembled work. When I started putting this collection together, I realized most of the fiction I’d been writing the last few years centered on death and transformation, and so I started by culling out any stories that didn’t adhere to that vibe. The result, I think, is a pretty lean and mean collection of stories that all seem in conversation with one another.

As for arranging the story order, I started by figuring out how to begin, and how to end. “See That my Grave is Kept Clean” was an easy choice to begin the collection. It’s one of the grimmest stories I’ve ever written, and becomes all about burying the reader in the earth. It sets the tone for everything to come. By contrast, “Till the Greenteeth Draw Us Down” is a lot more hopeful, if melancholy, and it felt like the perfect way to end the collection. You’ve travelled through all these dark places, and now are able to resurface, a bit worse for the wear, but alive and hopeful.

Connecting these two stories was just about feel and flow, I guess. Making sure that the transition from one story to the next feels logical. Not jarring. And I think the order I settled on works pretty wall.

Of course, a lot of readers like to skip around in collections, and that’s fine too. But if you read Death Aesthetic front to back, I’m hopeful it unfolds like one long journey through the afterlife, frightening, but ultimately reassuring.

Death might be our next step. But I don’t believe it’s the last one.